3. The corporate capture of agriculture

Jump to...

3.1 Corporate mergers and new economic players ‘disrupting’ food systems

Since the 1970s, agricultural inputs such as fertilisers and seeds, farmland, and the whole agrifood supply chain beyond food production (i.e., distribution and retail) have become increasingly concentrated in the hands of just a few agrifood corporations. Today, Global North countries and new emerging economies such as China and India host the headquarters of six major corporate conglomerates, which control 58% of the global seed market and 77.6% of the global agrochemicals market.41

The last decade – particularly between 2008 and 2018 – has seen corporate mergers consolidate previously separate areas of the agrifood sector under the umbrellas of just a few powerful multinational corporations. Manufacturers of fertilisers and agrochemical formulations, plant breeders, grain traders, and tractor manufacturers are often no longer run as separate businesses. Major corporates such as Bayer and Monsanto have simply become Bayer, and Dow and Dupont are now Corteva Agriscience, while ChemChina has incorporated the global pesticides company Syngenta.

As of 2022, at least 40% of the global trade in agricultural commodities is controlled by just ten corporations. In fact, this percentage may be even larger: global supply chains are opaque and much of the information is supplied by the companies themselves, which are among the most powerful and least transparent in the global supply chain.42

Known as the ABCD Group because of their initials – Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus – just four corporations have historically influenced the supply and prices of agricultural commodities and, unsurprisingly, have experienced large, surging profits since the Covid-19 pandemic.43 Recently, other new powerful companies have emerged, including China’s COFCO International, second only to Cargill in terms of global market share. Wheat, corn, and soybeans are the three most profitable agricultural raw materials traded worldwide, followed by sugar, palm oil and rice. Other important commodities include fibre, meat, and livestock.

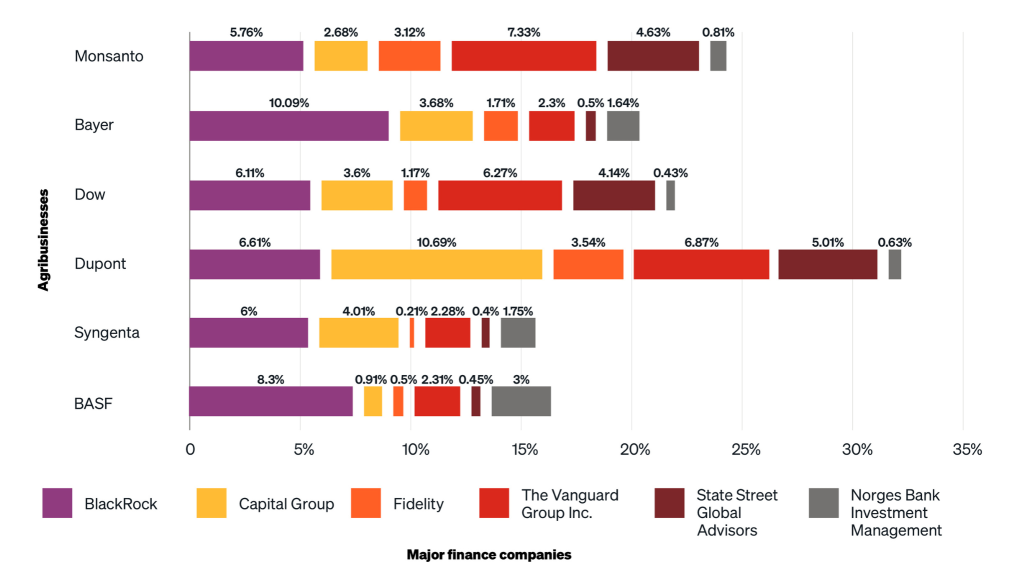

While these latest corporate mega-mergers across agricultural commodities trading, seeds, and agrochemicals are described by agribusiness corporations as a logical process of integration, this obscures the fact that the newly merged companies are largely owned by finance and investment companies. The shares held by these finance firms enable them to influence the agribusiness companies’ decisions – including company mergers. For example, Blackrock, Capital Group, Fidelity, The Vanguard Group, State Street Global Advisors, and Norges Bank Investment Management own important shares in agrochemical and seeds companies.

The last decade has also seen the growing influence of FinTech, or financial technology, and technology corporations on the agrifood sector; through increased involvement and investment in laboratories, fields, and the agrifood retail system. Big data has increasingly been deployed by corporations to strengthen their control of the global farming system, in which huge conglomerates have traditionally controlled strategic chokepoints of farm production. This data deployment occurs on multiple levels.

For example, technology linked to so-called ‘precision agriculture’ minutely monitors soil and field conditions. Drones originally developed for military purposes fly over crops, to supposedly gather real-time data. Farmers are then offered suggestions on crop irrigation, fertilisation, and the application of pesticides, as well as for general crop maintenance; based on decisions the tech’s algorithm has made by analysing the collected data. Based on the information gathered, the algorithm processes the data – owned by the corporation – to obtain market intelligence and induce farmers to buy more agricultural inputs (fertilisers, seeds).

Farmers are robbed of their decision-making capability over the whole production process by this new agricultural technology, whether via drone-collected data, or remotely controlled tractors.44 Farmers are stripped of the freedom to plant traditional or other alternative seeds or apply other forms of soil fertilisers or pest control.

New digital technologies are also used in the retail sector: Amazon uses big data to gather information and target its customers more accurately. It now sells organic groceries through its own retail system Amazon Fresh, while gathering more information about the genome over on the production side, which it is becoming increasingly capable of mapping and genetically modifying through precision technology.45 The Big Tech corporate giants, which include Amazon, are increasing their monopoly control over the intellectual property needed for farming. Farmers will be pushed further into becoming subcontractors for corporations, amidst comprehensive deskilling and a loss of control over the intellectual property which in principle is common property, resulting from thousands of years of decentralised farming.

So far, this technology is mostly rolling out in the Global North, as the financial incentive to replace human labour with technology in many Global South countries is not yet sufficient, even though such a rollout would be profitable for big companies. However, one of the world’s leading producers and distributors of pesticides and seeds, Bayer, is deploying apps across Argentina and Brazil – Latin America’s agricultural colossuses – on very large plots of land, collecting farmer data in exchange for advice and discounts.

In Africa, Vodafone’s subsidiary, Safaricom, is providing millions of small farmers in Kenya with digital platforms providing chatbot assistance, access to crop insurance and agricultural inputs such as seeds, pesticides, and fertilisers. Although such platforms provide financial services to rural people who would otherwise not have access, these platforms do not come for free. To access their own financial services, farmers must buy the agricultural inputs promoted and sold to them on the platform, via credit at high interest rates; follow the chatbot indications on crop insurance; and receive payments via a digital money app, which comes with a fee. As outlined in research conducted by GRAIN, a non-profit organisation supporting small farmers and food sovereignty social movements, this is contract farming on a mass scale.46

Another technological trend in the Global North is the early yet rapidly growing move to lab-grown meat substitutes.47 There is a rising tendency in Global North public discourse to blame carbon emissions on animal farming, while sidestepping the fact that different forms of animal farming produce vastly different emissions profiles.48

In fact, lab-grown meat substitutes will change rather than fix underlying problems, since production is based on large-scale monoculture. Most lab-based meat requires glucose, amino acids, and vitamins and minerals produced out of inputs derived from industrial monoculture. Lab-grown meat is only being rolled out on a small scale, partly because the apparatus needed for growing organisms under controlled conditions – bioreactors – are staggeringly complex to design and build.

However, the lab-grown meat project may yet be deployed as a pretext for further theft of Global South land, as well as for new market opportunities for corporate profits. Lab-grown meat paradoxically represents a multi-billion US dollar opportunity for the very corporations controlling the industrial livestock and farming sectors. The world’s largest agricultural commodities trader, Cargill, and the largest global meat trader, JBS Foods, have heavily invested in lab-based meat and plant-based substitutes.49

The alternative protein market is now characterised by giant companies which combine both industrial meat production and its alternatives – creating 'protein' monopolies. Well-meaning consumers of alternative proteins may not realise they are buying into the same giant meat companies that are operating the biggest factory farms, contributing to deforestation and forced labour, and slaughtering millions of animals every day.

3.2 The corporate capture of UN policy spaces

The corporate capture of agriculture is occurring institutionally across policy spaces, including through rising corporate influence over the United Nations, such as at the UN Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) that was organised in 2021.51

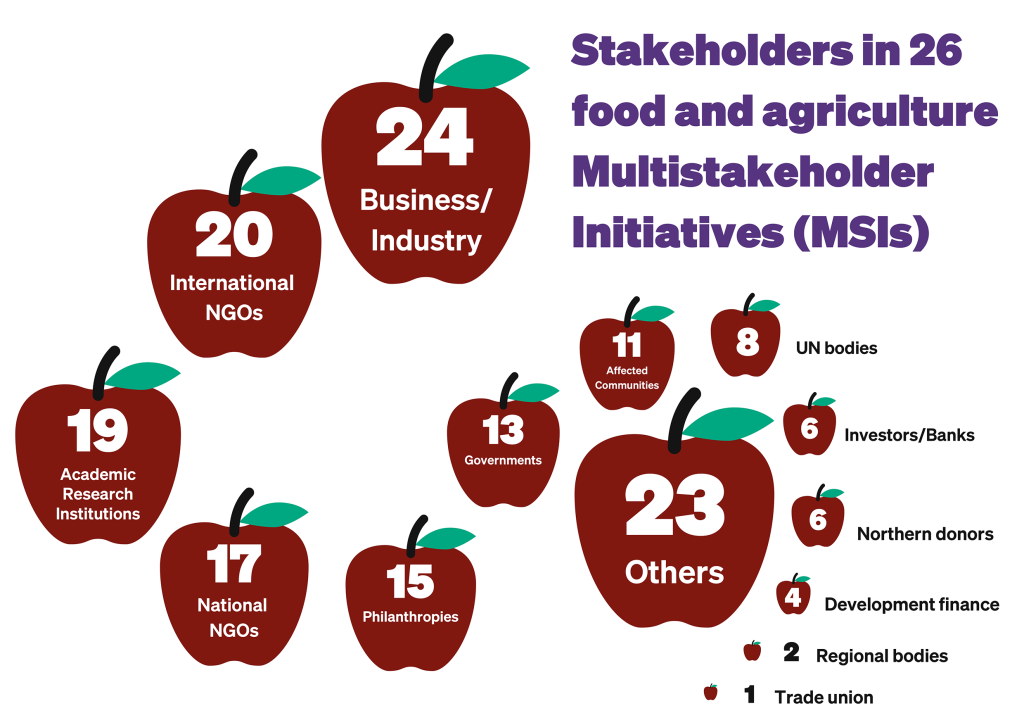

The UNFSS has been slowly moving away from multilateral negotiations and the alliance of states of all political affiliations, towards what has been called ‘multistakeholderism’ (a type of multi-stakeholder governance), which upholds the rights of corporate monopolies as equal partners to democratic, sovereign, or representative states and peoples’ movements.

The 2021 UNFSS was heavily criticised by over 550 civil society organisations for the influence given to corporations, big data, and the financial sector in shaping its agenda – including the involvement of the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and large agribusinesses. The WEF, which is leading the development of ecological-agricultural systems, has since signed strategic agreements with the UN, one of the precursory aims of its presence at the UNFSS.

The co-option and conversion of these important influencing spaces by monopoly corporations to serve their own capitalist agenda is now proceeding at a rapid pace. The Chair of the 2021 UNFSS Advisory Committee was Amina J. Mohammed, a high-ranking UN official who happens to be on the board of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Global Development Program; while the UN Special Envoy to the UNFSS, Dr. Agnes Kalibata, is President of Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), a self-identified non-profit founded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. AGRA promotes the spread of industrial agriculture and agribusinesses in Africa. It has been heavily criticised by academics and civil society organisations for failing to meet its goals for increasing crop yields, while undernourishment increased by 30% in the countries where it has active programmes.52 AGRA, the WEF, and the Rockefeller Foundation – a patron of the Green Revolution – are amongst the stakeholders turning the UNFSS into a forum for corporate agribusiness.53

Another force within international policy spaces is EAT, a global non-profit start-up that claims to be dedicated to “transforming the global food system through sound science, impatient disruption and novel partnerships”. It comprises EAT Forum, EAT Foundation, and the EAT-Lancet Commission on Sustainable Healthy Food Systems. EAT receives large amounts of funding from Aviva, Nestlé, Fazer, and Bayer – all of which are beginning to develop and sell plant-based products.

These corporate institutions are pushing their own agendas through one of the strategic documents of the UNFSS called Action Track 3, to “boost nature-positive production.”54 This is how nature-based solutions and fragments of an agroecological technical agenda are able to enter mainstream policy: when presented and welded to a corporate vision.

3.3 The climate crisis and corporate greenwashing

The climate crisis and its ongoing impacts on food production are a focus for debate and resistance among peasant movements.

The last decade has seen the rise of corporate greenwashing, in the form of so-called ‘nature-based solutions’, which supposedly seek to protect ecosystems to address societal challenges. Proposed by corporations, those responsible for the majority of global greenhouse emissions, nature-based solutions are false solutions to the climate crisis, ignoring peasant and Indigenous people’s knowledge, and are often positioned ambiguously, allowing corporations to twist their meaning. While these new forms of corporate greenwashing are tied to climate-friendly corporate social responsibility practices, there is a danger they are co-opted as just another strategy for corporations to increase their profits.

Yet, because many consumers and countries in the Global North are detached from the agricultural world and its means of production, so-called nature-based solutions become an alluring concept with the impacts on southern producers not taken into account. In fact, false, greenwashed solutions such as carbon offsetting require purchasing and grabbing vast areas of land in the Global South.55 The global agriculture sector is a major contributor to global greenhouse emissions, and a hugely complex part of the puzzle to resolve. It ranges from forestry, deforestation and land management to petrochemicals and tractors, to soil erosion and carbon loss, and covers the transportation, processing, and shipping of food products the world over, from Argentina to Alaska.

Industrial agriculture creates between 21% to 37% of total net greenhouse gas emissions including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. These emissions result from a wide range of land-based agricultural activities and cause ecological degradation, which is being exacerbated by climate breakdown:

- Soil erosion is happening at 100 times the rate of soil formation in places, with climate breakdown worsening this dynamic. The total area of the world’s drylands experiencing drought is increasing yearly. Climate breakdown is particularly impacting food security in soil-degraded or desertified zones; as the weather warms, rains roam from their normal ranges, and extreme weather events from floods to droughts damage food production. Meanwhile, across the tropics and sub-tropics of the Global South, crops move closer to the limits of their survival as yields sink. African savannahs and their pastoral populations are seeing lower animal growth rates. Across Africa, and in mountainous zones of South America and Asia, pests and diseases are infesting agricultural lands.56 Large-scale, industrial agriculture is a major driver of these trends.

- Widescale deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is destroying one of the Earth’s important carbon sinks; while global emissions of carbon dioxide and methane are increasing from the industrialised soy plantations and cattle-rearing operations which are replacing it, including from the fumigation and large-scale harvesting of soy. The Amazon rainforest’s carbon-absorption capacity is shrinking, while agribusiness monopoly interests fatten wallets and portfolios in Brazil and the United States. Other important areas of biodiversity in Latin America, such as the Cerrado in Brazil and the Gran Chaco between Paraguay and Argentina, are experiencing the expansion of the soy frontier, with dramatic consequences on biodiversity and local livelihoods, as local people are expelled from their land, populating new slums in cities across the continent.57

- Elsewhere, deforestation due to peat extraction in the UK or for monocrop palm oil plantations in Indonesia is a major contributor to global emissions.58 In Brazil and Indonesia, monocrop deserts replace vibrant polycultures, which protected biodiversity and provided people with the means to support dignified lives, and even market some of their crops.

a. Agrofuels

Corporations are promising to deploy agrofuels, derived from plants instead of fossil fuels, to achieve ‘net zero’ emissions from airplanes and cars by 2030 or 2050, or in so-called ‘hard to decarbonise’ sectors such as steel production and concrete.59

These ‘solutions’ tend to come into conflict with smallholders’ need for food, driving peasants off the land and into urban slums. They rest on a narrow vision of the necessity of protecting certain sectors. There is no need to build with concrete and steel in places where wood and bamboo can be used instead.60

b. Carbon offsets

Another false solution is carbon offsetting. The idea being carbon dioxide emissions generated through a specific activity can be calculated and paid off, or ‘offset’, via a scheme to remove the carbon from the atmosphere, such as tree planting. One of several ‘natural climate solutions’ increasingly embraced by powerful development organisations and corporations,61 mass tree planting campaigns are seemingly a great idea: use nature, namely trees, to turn carbon dioxide into carbon using nothing more than solar energy. In fact, the record of tree planting is abysmal, while sowing monocrops of trees is often ecologically inappropriate, not reflecting the original biodiversity. One of the largest global tree planting projects in India has almost nothing to show for it.62

Firstly, tree planting can drain the water table, forcing away people whose livelihoods depend on the use of land.63 Secondly, such ‘solutions’ often claim that land has been deforested when it was historically simply spotted with trees.64 Thirdly, because these ‘solutions’ use monocrops, they sidestep participatory solutions, which may be less attractive and marketable, although potentially much more effective; resting on farmers growing polycultures of useful trees, rather than a narrow range of fast-growing trees to be ‘banked’ for carbon credits. Fourthly, protecting existing forests ought to be a higher priority than planting new ones, since old forests store far more carbon dioxide per hectare, while providing livelihoods for forest-dwelling peoples to use fruits, fuel, or other goods secured from agroforestry.65

These ‘solutions’ – even where they truly are solutions – are frequently sold as carbon credits or turned into ‘offsets’. Nature-based solutions are excuses for corporations to continue burning valuable fossil fuels, under the guise of ‘net zero’ emissions. Global North corporations offload the costs of climate breakdown onto farmers and local communities in the Global South for what are often paltry sums, so that the polluters can keep on polluting. The Global South needs absolute reductions in emissions starting today, rather than ‘natural climate solutions’ which ‘offset’ the extra carbon dioxide corporations have dumped into the atmosphere.

Other ‘nature-based solutions’ proposed at the 2021 UNFSS included Bayer-sanctioned techniques to sow carbon into soil (carbon farming)66 and digital farming apps to verify and pay farmers: satellites verify the carbon sequestration, creating a massive new carbon market and moving towards commodifying nature, such as the soil’s capacity to absorb carbon.67

c. Other technological fixes

Among the ideas brought forward and applied in Global North countries as innovative technological responses are sometimes useful solutions for small-scale use in urban contexts and urban agriculture. One example is vertical farming, a form of food production (mostly for horticulture) which uses very tall structures to saving farming space. Another example is the use of hydroponics, a modern farming technique (sometimes combined with vertical farming) to grow plants in a soil-less environment using only water. While these techniques may be useful in some contexts, the main goal of these methods is to produce food and compensate for the lack of available land. Rich corporate investors, such as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, are investing large sums in start-ups which are using this technology.68

However, critics fear that this model of food production has a strong political message: that land is not for those who work it and that ‘disruptive innovations’ will solve the issue of hunger or the climate crisis. The problem with this model is that it uses technological fixes that do not get to the root of the problem, the lack of land to produce food. It ignores the fact that land is being grabbed across the world and particularly in the Global South, and it is being concentrated into the hands of the few.

Technological advances have also seen the development of genetically modified seeds69 and more recently CRISPR technology for gene editing. GM crops are now widely grown across the Americas (such as corn, soy and wheat); engineered to produce higher yields and resist changes in weather patterns or extreme climatic events.

The real solutions to the lack of land for agriculture would be systematic, popular and comprehensive agrarian reforms that redistribute access to land to peasants and Indigenous people, who preserve 80% of the world’s biodiversity.70

4. Individual responsibilty

Media and corporations in the Global North currently place a great deal of emphasis on individual responsibility for the climate crisis: people are told to drive less, use less plastic, go vegan, and use less energy. Although international shifts in how much people consume would lead to Global North consumers using less resources, such changes cannot be simply oriented around individual responsibility. We need planning, which means mass international social and political organising to bring about lasting, structural change.

While boycotts are a useful tool of political organising – such as the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine; and the 1970s boycott of Nestlé products, over its aggressive marketing of baby formula instead of breastfeeding in the Global South – the fact remains that the major sources of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions are fossil fuel companies, and the agrifood monopolies and deforesters. Placing responsibility on individuals diverts the focus away from corporations – the biggest polluters with the most responsibility for the climate crisis and ecological breakdown. It is not a solution at all.

The scale of the challenge is complex and interconnected, and narrow measures focused on individual responsibility are not solutions to the multiple crises of poverty, inequality and injustice, and global heating. There is an opportunity to rethink how the global systems for major sectors like agriculture and food could work in ways that prioritise the needs of people and the planet.

A just transition of the global food system means adopting food sovereignty as a pathway to restore the Earth’s biodiversity, protect the environment while protecting the rights of food-producing people, and protecting the rights of all people to nourishing food and clean safe water.

Only a global food system based on food sovereignty can deliver a sustainable and equitable alternative to feed the world’s people in ways that keep us below a temperature rise of 1.5°C, with everyone doing their fair share of effort to meet climate imperatives. A model based on food sovereignty is also the only way to ensure issues of inequality and poverty are addressed, including redressing historical injustices and systems of exploitation rampant in current global food production; it also offers the best way in which to ensure food production thrives within planetary boundaries.

- 41//etcgroup.org/content/food-barons-2022

- 42Ibid.

- 43//www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/aug/23/record-profits-grain-firms-food-crisis-calls-windfall-tax

- 44//doi.org/10.1111/joac.12470.

- 45As an example, the CRISPR technology is used to refer to a variety of systems that are programmed to be able to target sections of genetic code, and to in turn edit DNS in certain locations. In this way, researchers have the means to modify genes permanently in organisms and living cells and could in the future perhaps correct mutations and target the genes which lead to disease.

- 46//grain.org/en/article/6595-digital-control-how-bigtech- moves-into-food-and-farming-and-what-it-means (accessed August 2022)

- 47//vegnews.com/2021/10/usda-lab-grown-meat

- 48//newsocialist.org.uk/red-vegans-against-green-peasants/; Ian Scoones, “Livestock, Methane, and Climate Change: The Politics of Global Assessments,” WIREs Climate Change n/a, no. n/a: e790, accessed July 19, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.790

- 49//ipes-food.org/pages/politicsofprotein

- 51 661552.

- 52//www.foodsystems4people.org/multistakeholderism-report/ Accessed August 2022;Timothy A. Wise, 2020. “Failing Africa’s Farmers: An Impact Assessment of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa” Tufts University. https://sites.tufts.edu/gdae/files/2020/07/20-01_Wise_FailureToYield.pdf

- 53 Wheat, Genes, and the Cold War (Oxford University Press, 1997).

- 54Elizabeth Hodson et al., “Boost Nature Positive Production,” Report (Center for Development Research (ZEF) in cooperation with the Scientific Group for the UN Food System Summit 2021, April 2, 2021).

- 55//grain.org/en/article/6877-an-agribusiness-greenwashing-glossary

- 56//www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/08/4.-SPM_Approved_Microsite_FINAL.pdf

- 57//www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/05/screaming-hairy-armadillo-the-forest-the-world-forgot-gran-chaco and on Brazil’s Cerrado: https://www.ft.com/content/c70e8db4-11c4-42b3-808d-016e413253cd

- 58 e70323.

- 59//www.energy-transitions.org/publications/towards-a-low-,carbon-steel-sector/

- 60 Pluto Press, 2021), Chapter six and references.

- 61PU UNDP, “The next Frontier-Human Development and the Anthropocene,” Human Development Report 2020, 2020.

- 62 105864.

- 63“Are Huge Tree Planting Projects More Hype than Solution?” Yale E360, accessed July 25, 2022, https://e360.yale.edu/features/are-huge-tree-planting-projects-more-hype-than-solution

- 64//doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.003

- 65//doi.org/10.1890/14-1154.1; Alice Di Sacco et al., “Ten Golden Rules for Reforestation to Optimize Carbon Sequestration, Biodiversity Recovery and Livelihood Benefits,” Global Change Biology 27, no. 7 (2021): 1328–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15498; McGarvey et al., “Carbon Storage in Old-Growth Forests of the Mid-Atlantic.”

- 66https://cropscience.bayer.co.uk/bayer-carbonprogramme/

- 67 Tulika Books, 2020), 180–97.

- 68//tcrn.ch/2tgumSl (Accessed November 2022)

- 69//waronwant.org/resources/food-sovereignty-report

- 70 Preparing for the Decade of Family Farming (2019–2028) to achieve the SDGs”, 2018.