10. Food and agricultural workers in the UK: organising against exploitation

Peasants and other people working in rural areas have the right to form and join organisations, trade unions, cooperatives or any other organization or association of their own choosing for the protection of their interests, and to bargain collectively. Such organisations shall be independent and voluntary in character, and remain free from all interference, coercion, or repression”.

The unjust global food system is sustained by trade agreements negotiated in the interests of Global North countries and multinational corporations; by the role of large profit-driven retailers and supermarkets, and by exploitation of the agrifood workers in their supply chains.

Supermarkets’ low prices in Global North countries such as the UK are the result of low wages paid to food and farmworkers in the Global South. This model of exploitation is replicated in the Global North among marginalised workers who have migrated from poorer countries.

In the EU, more than a third of horticultural crops (cultivation of fruits and vegetables), and almost half of its fruit, comes from labour-intensive farms from Italy and Spain that employ exploited seasonal and foreign workers, usually from the Global South, who are often undocumented, with few legal rights and little protection in the countries they work in.127

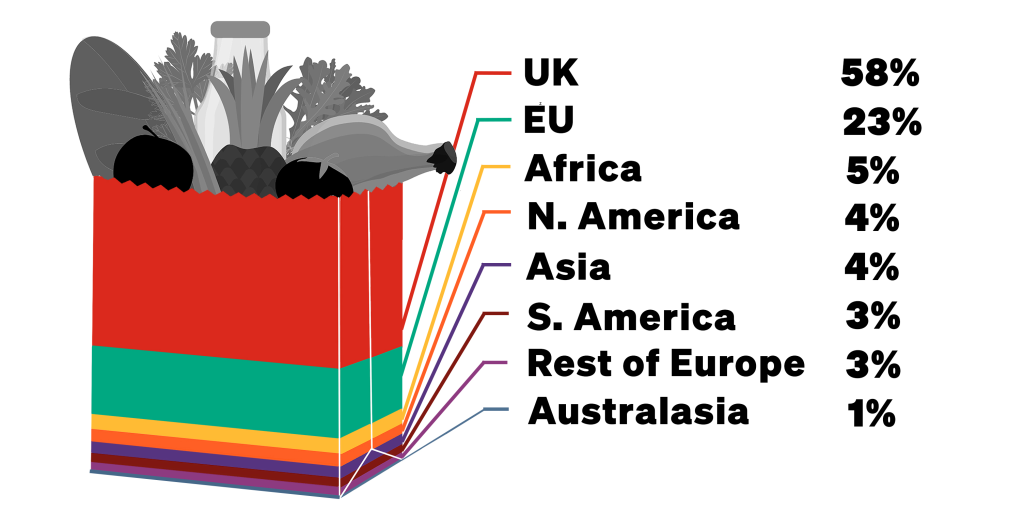

The UK relies on trade deals to bring in cheap produce as part of its post-Brexit trade strategy, such as the recently signed Morocco deal (2019), while growing only 58% of food consumed in the country.

According to 2021 statistics from the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the leading foreign suppliers of food consumed in the UK were countries from the EU (23%), Africa (5%), Asia (4%), North America (4%) and South America (4%). At the same time, the agricultural and food processing sectors in the UK employ a workforce composed mostly of foreign workers.

Workers in labour-intensive UK sectors such as horticulture and meat processing face high levels of exploitation and deregulation, particularly in England. Since the abolition of the English Agricultural Wages Board in 2013, the exploitation of foreign workers has increased: farmworkers in England do not have statutory protection for their pay and conditions, whereas Scotland and Wales have retained their agricultural wages boards, and foreign workers in these countries still receive statutory protection. Foreign workers in England are therefore left more exposed to “low wages and poor conditions in a system where markets do not value agricultural workers as vital contributors to our food chain”.128

In 2021, across the UK 99% of seasonal workers in horticulture came from outside the country,129 and 62% of those employed in meat processing were EU nationals.130

Foreign workers are the backbone of the UK’s food supply chain, without whom the UK food system would all but collapse, yet they face rampant labour exploitation. Research by the University of Nottingham surveyed nearly 500 Bulgarian and Romanian workers employed across the UK agrifood industry. It found that foreign workers face abuse, exploitation, and debt; a situation which has grown worse since the Covid-19 pandemic.131

Nearly a fifth of those surveyed reported emotional abuse or threats at work, with 11% saying they had not been issued payslips, a work contract, or a P45 form (which includes salary and taxes paid to date once the employment contract is over). One in ten were paid below the minimum wage, while 7% reported not being allowed to take holiday, not receiving any holiday pay if they did, and having wages withheld. One in ten paid a fee to an individual, agency or employer to secure their job, despite the practice being illegal in the UK and in their home countries. Because of this, researchers believe that such experiences of exploitation are significantly under-reported.

The UK trade union Unite has been organising foreign workers in the British agricultural and food sector for years, an issue that has long been a challenge because of the transient nature of the workforce – but which is seeing positive results.

FOCUS: Organising workers at 2 Sisters Food Group’s poultry factory in Sandycroft, Wales

The 2 Sisters Food Group’s factory in Sandycroft, Wales, is one of the largest poultry processing sites in the UK. Although Unite has had a union recognition agreement with the factory for many years, Unite Regional Officer Brian Troake explained that it has been a long struggle to recruit enough members to have much impact:

We’ve struggled with the membership because it’s such a transient workforce. People will start work at 8am as a new employee and they’ll quit by 8.30am. The work is enormously physically demanding, and the wages and treatment of the workers is so poor. Compounding the problem for union organising in the sector is not just one language barrier, but dozens.

There are 32 different worker nationalities at the 2 Sisters Sandycroft site, with almost as many different languages spoken. This is reflected in the University of Nottingham study; 41% of foreign workers surveyed said language was the most significant barrier to flagging problems in the workplace.

After years of struggling to increase membership, Brian and his union colleagues decided to take a new approach, one that yielded astounding results, with 600 new members recruited in 18 months. They conducted a mapping exercise and went about targeting different communities by identifying leaders in those communities.

Unite’s Site Convenor at 2 Sisters Sandycroft, David Imre, had a crucial role in organising and mobilising workers. Originally from Romania, David moved to the UK in 2016, only joining Unite in 2019. Since then, he has gone from union member to rep to convenor, and has single-handedly recruited hundreds of members. David said his ‘proudest moment’ was recruiting 89 members in a single day.

So, what is the secret to his success? “You need to listen to people,” David explained. “And sometimes that may involve listening to them about their personal lives outside of the workplace. That’s how you build trust. People need to know that you really care.”

The union plays an important role in supporting workers and their families and working to address the issues and needs they raise. At a site where 80% of the workforce are foreign workers, David’s ability to speak five languages is indispensable.

“Especially when people are angry, scared or emotional, it’s hard for them to communicate in a second language,” David noted. “We need to be able to talk to members in their native language.”

With numbers comes power – and union members at 2 Sisters Sandycroft began to realise just how much power they could wield when they stuck together.

In 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, management dug their heels in when the workforce demanded better Covid health and safety measures; but thanks to the increased membership and the insistence of David and his team of reps, management relented.

And in 2021, members secured an unprecedented pay deal, where the lowest paid workers – accounting for 40% of the workforce – saw their pay increase by 6.4% at a time when inflation was only just hovering above 2%. This pay rise took their pay above the UK’s real Living Wage for the first time in the site’s history.

Those working in ‘manual debone’, about a fifth of the workforce, saw their pay skyrocket by more than 10%, while those in the ‘kill and hang’ part of the business saw a pay increase of 7.7%. The deal also secured an additional day’s holiday for everyone.

“Because we are so strong now with hundreds more members, it was not so much of a pay claim last year, it was more of a pay demand,” Brian explained. “It’s been really empowering and inspiring for people, myself included. It’s not often you go into pay talks with such a strong negotiating position.” Brian said he is eager to replicate this success at other food processing sites across the UK – and David is hopeful it will happen, as long as migrant workers’ voices are truly heard.

“Finding migrant reps should be at the forefront of our efforts,” he said, adding that migrant reps are also essential because they truly understand the unique migrant worker experience.

“Think about it – you come from a foreign country, you can’t speak the language, you’re often badly treated at work and in the wider community. These people have nowhere to go and no one to turn to. We need to help them.”

Above all, David urged all food and agriculture workers to join a union. “The more of us that we are, the more power we have to make big changes in our workplaces,” David said. “If there’s a problem, we can fix it – but that’s only true if there are enough of us to show we have the power. We’ve proved that it works.”

Organising foreign workers in UK food industries has become increasingly important since the UK government’s post-Brexit introduction of the seasonal worker visa scheme, which Unite believes renders foreign workers more vulnerable to exploitation. Whereas previously workers from EU countries came to the UK under EU freedom of movement, the UK’s seasonal worker visa scheme is tied to jobs; if a worker loses their job, they lose their right to work in the UK. Consequently, workers are less likely to report abuse or exploitation, for fear of being sacked.

In 2022, a joint investigation by the Guardian and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) exposed how fruit pickers from Nepal on seasonal migrant worker visas were illegally charged thousands of pounds by recruitment agencies to work on UK farms.133 The investigation highlighted how the UK government body tasked with licensing labour providers and protecting vulnerable and exploited workers, the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), is poorly funded and lacking the resources required to tackle rising exploitation under the new visa scheme.

The Guardian and BIJ noted that the UK Home Office’s funding for the GLAA was a mere £7 million in 2021, less than the Home Office spent on publications, stationery and printing.

In 2021, the UK government announced an expansion of the visa scheme as part of its National Food Strategy yet failed to consult Unite, or any other trade union, despite Unite representing over 100,000 workers in the food, drink, and agriculture sector. Unite has expressed grave concerns that without any additional funding for labour rights enforcement or changes to the visa scheme to protect foreign workers, any expansion of the scheme will only further undermine pay and terms and conditions in a sector that is already rife with low wages and exploitation.

The UK government’s strategy was based on an initial review carried out across 2020 to 2021 by Leon chain restaurant co-founder Henry Dimbleby, the first of its kind since wartime rationing 75 years ago. What was supposed to be a significant and historic review of the UK’s food system fell short after it failed to adequately highlight the contributions or issues faced by the food sector workforce. In the 275-page review, there was barely any mention of jobs, workers or employment.134

While the UK government continues to show little interest in the fate of the foreign workers on whose efforts the entire UK food system depends, Unite believes that trade unions and other grassroots organisations must prioritise directly engaging with and empowering foreign workers.

The 2 Sisters in Sandycroft case illustrates that this approach can work, and key to its success was that it was worker-led – with migrant workers themselves organising each other.

- 127For a detailed analysis of the gangmaster phenomenon in Mediterranean Europe and the “dirty supply chain”, we recommend the report (EU)xploitation. Gangmastering: The Southern Question. Italy, Spain and Greece, Maria Panariello (ed.), F. Ciconte, A. Fotiadis, S. Liberti, M. Paone, Terra! Association, 2021. https://cdn.associazioneterra.it/media/files/euxploitation-eng-web.pdf

- 128Sustain, “Why would anyone want to pick our crops? Securing decent pay and conditions for agriculture workers in England”, 25th July 2018 https://www.sustainweb.org/news/jul18_workers_briefing_launch/

- 129Melanie Gower, Sarah Coe, “Recruitment Support for Agricultural Workers”, House of Commons Library 23rd May 2022 in https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CDP-2022-0094/C…

- 130https://britishmeatindustry.org/industry/workforce/

- 131Hajera Blagg, Unite the Union (2022). The following section draws on a report from Unite the Union on foreign workers in the UK.

- 133Emiliano Mellino, Pete Pattisson and Rudra Pangeni, “Migrant fruit pickers charged thousands in illegal fees to work on UK farms, investigation shows”, The Guardian, 27th May 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/may/27/migrant-frui… (Accessed August 2022).

- 134Henry Dimbleby, National Food Strategy for England, July 2021, in https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-food-strategy-for-e… Commenting on the government’s food strategy, Unite national officer Bev Clarkson said, “It was no surprise the strategy contains nothing to fix the poverty pay and awful working practices that are at the root of the sector’s endemic staffing problems. Ministers are not interested in addressing these things. If it were, they would sit down with Unite, which represents many thousands of workers from farm to fork.”